Serendipity refers to a pleasant and unexpected phenomenon, occurring due to chance, and mostly happens when we are looking for something else. Serendipity is enjoyment when it appears in our daily lives, but did you know that it has also led to significant discoveries and developments in science and technology?

It may seem counterintuitive to refer to fate/coincidence when talking about science, considering scientific research is usually conducted in a very systematic, analytical, and controlled way. However, we know now that chance is a crucial determinant in research and has been responsible for some significant past discoveries.

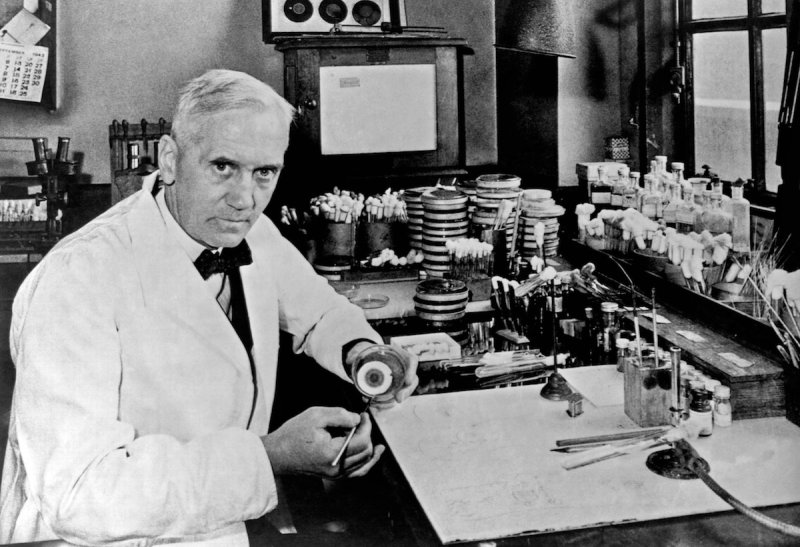

The curious case of Alexander Fleming

The most well-known example of serendipity in scientific discoveries is, perhaps, the accidental invention of the antibiotic penicillin. In 1928, when Alexander Fleming returned to his laboratory at St. Mary’s hospital after being away on vacation, he noticed a culture dish of the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus that he had accidentally left on his bench had been contaminated with mold — and it was killing the bacteria. The mold was later identified as Penicillium rubens, a rare species capable of producing the antibacterial substance we now know as penicillin. When Fleming first shared this remarkable finding, he did not get enough attention from the scientific community. It took ten years until two other scientists, Howard Florey and Ernst Borris Chain, realized the potential value of penicillin and picked up what began as a laboratory curiosity to develop it into a practical drug. For this vital discovery and development, the three of them later shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945. To this day, the curious series of lucky events that led to the discovery of penicillin has left many scholars wondering. Even Fleming himself admitted that the discovery was “a complete accident”.

“One sometimes finds what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.”

Alexander Fleming

The lucky error that elevated a vaccine’s potency

Let’s look at one more example that is more recent and currently relevant. If you are following the race for COVID-19 vaccines, then you must have heard of one of the frontrunners developed by the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca with the University of Oxford (UK). Early reports from the clinical trial results are baffling scientists — they found a striking difference in the efficacy of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine depending on the amount of vaccine given to a participant. Why different dosing was used in the first place was actually not intended: they planned to provide a month apart of two full doses, but due to a mistake, some trial participants were accidentally given a lower first dose. Here’s where it gets interesting: this unintended group of people actually showed better effects — according to the preliminary results, the vaccine is 90% effective in protecting them against COVID-19, compared with 62% in people who got two full doses. The reason why they had the lower amount is purely serendipitous, and it appears this lucky mix-up might have boosted the vaccine’s efficacy.

Is it just about luck?

Looking at these examples, it seems that just being in the right place at the right time can lead one to serendipitous discoveries, right? So, does this mean that just anyone could have discovered penicillin? Or any other major scientific discoveries for that matter? Is serendipity all it takes to uncover great science?

“The seeds of great discoveries are constantly floating around us, but they only take root in minds well-prepared to receive them.”

Joseph Henry (first director of the Smithsonian)

More important than getting the chance to encounter the unexpected is, of course, having the background knowledge and skills to recognize what is there and separate the meaningful from the irrelevant: whether what one is seeing is indeed the tip of a great, submerged iceberg or just a passing block of floating ice. So, one must be “lucky” not only in coming across serendipity, but also in having the chance to put their skills to use and succeed in making a discovery.

Before Fleming, at least 28 other scientists had reported the killing of bacteria by mold. Still, they all decided to see it as an unfortunate mistake rather than an opportunity for discovery. People are often oblivious of the exact thinking processes preceding a discovery and hence cannot make complete sense of what is happening. So why exactly did Fleming choose to pursue the promising lead that was ignored by so many scientists before him? This is where expertise and scientific experience come into play. Nine years before the penicillin discovery, Fleming observed that the bacteria in one of his culture dishes died after being contaminated with his nasal drippings. This incident led to his discovering the bacterial enzyme, lysozyme, which is found in nasal mucus. Sounds familiar? Indeed, this very experience and further investigation into lysozyme are what sparked his interest in antimicrobial research. Thanks to this, it made him the perfect eyewitness and a receptive observer for the extraordinary fate that led to the invention of the life-saving antibiotic.

Optimizing opportunities for serendipity in science

The phenomenon of serendipity is clearly beyond our control, and we might not even be aware of it when it does occur. Instead, can we do something to develop the skills to be more receptive towards it? Or to create an environment conducive to it?

One important attribute is to keep our minds open and curious, willing to examine the data from different perspectives, and challenge existing dogmas. Currently, there is an unfortunate paradigm in science where positive results (those which agree with initial hypothesis/are expected to happen) are favored over negative ones (those which are unexpected), which ultimately debilitates scientists from thinking ‘too loud’ and rather biases them to conduct studies that are more likely to generate predicted results (see Tiago’s post here which nicely elaborates this and many other issues in our current scientific system). Instead, as scientists, we should make it normal to examine and communicate unusual happenings. Having people from diverse disciplines working together, for example, can encourage frequent and open communication in a group setting. This way, irregular observations that do not conform with a scientist’s field of interests can be talked over with colleagues who may find an application for the new information.

Although often associated with a neat and logical process, in real life, science is not only about conventional thinking and methods. Most discoveries come not only through reasoning alone. Therefore, it will be good to appreciate and embrace the importance of serendipitous events in science. After all, in many cases, findings that contradict our initial hypothesis are what help us generate important research ideas leading to fascinating revelations.

Further readings:

– Stories on many more accidental discoveries in science

– Biography of Alexander Fleming by Gwyn McFarlane “Alexander Fleming, the man and the myth”